Most recent BDB-Lab papers

BDB-Lab Links

Major Projects

Other Links

Lab Members

Twitter feed

Tweets by BigDataBiologyCryptic AMPs from Prokaryotes: an investigation with AMPsphere and proGenomes2

by Anna Vines, Célio Dias Santos Júnior, Luis Pedro Coelho.

tl;dr. In our research, we aimed to investigate in silico the production of cryptic antimicrobial peptides (cryptic AMPs) by prokaryotes. Using AMPsphere and the proGenomes2 representative genomes dataset, we found >50,000 potential cryptic AMP candidates produced by microbes. We further analysed the properties of these cryptic AMPs by assessing their position within their precursor protein, comparing their antimicrobial score to the protein around them and through ascertaining which enzymes could release them through proteolysis. We conclude that there is a potential cryptome full of AMPs that may shape the relationship between different prokaryotes in the environment.

A quick introduction to cryptic AMPs

Cryptic peptides - sometimes known as cryptides - occur when a larger protein is broken down through proteolysis (Pizzo et al., 2018). The properties of the resulting cryptides can be hard to predict, with some cryptides serving similar purposes to the precursor protein while others have entirely new properties (Autelitano et al., 2006). Cryptic antimicrobial peptides (cryptic AMPs) are thus cryptides with antimicrobial properties, and cryptic AMPs may or may not originate from an antimicrobial precursor protein. The antimicrobial nature of these peptides is often as a result of their cationic nature, which allows them to disrupt the surface membrane of microbes (Bradshaw, 2013).

Cryptides have attracted attention due to the growing understanding of their role in the diversity of the proteome, given that the properties of cryptides may vary from those of their precursor proteins (Autelitano et al., 2006). Specifically, cryptides with antimicrobial properties can be notable for two reasons; firstly, they provide a new avenue for the discovery of compounds with potential clinical applications and, secondly, they may result from a host response to antimicrobial resistance within pathogens. Given the growing threat of resistance towards conventional antimicrobials, much research on cryptic AMPs has focused on these potential therapeutic applications of these peptides (Pizzo et al., 2018). However, cryptic AMPs that originate from precursor proteins with antimicrobial properties also present an intriguing aspect of eukaryotes’ responses to antimicrobial resistance. While bacteria may develop proteases which can disarm antimicrobial peptides produced by eukaryotes, these proteases may then in turn release a new, cryptic, antimicrobial peptide which in turn destroys the bacteria (Pizzo et al., 2018).

What research has been done on cryptic AMPs in the past?

Previous research on cryptic AMPs has predominantly focused on cryptic AMPs produced by eukaryotes. Milk and its cryptides have been the subject of much investigation, with biologically-active protein bovine lactoferrin being particularly notable. Lactoferrin has a wide variety of properties, including antibacterial and antiviral capabilities. When broken down, this protein releases two different cryptic AMPs: bovine lactoferricin and bovine lactoferrampin (Pizzo et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, there remain numerous gaps within the literature on cryptic AMPs. While Pizzo et al. identified a potential cryptic AMP candidate in silico from archaeon Sulfolobus islandicus (Pizzo et al., 2018), whose antimicrobial properties were later confirmed in vitro (Roscetto et al., 2018), there remains vanishingly little research into cryptic AMPs produced by prokaryotes. We could not find prior examples of research into cryptic AMPs produced by prokaryotes using large-scale environmental datasets.

How has the BDB-Lab worked towards filling the gaps in the literature on cryptic AMPs?

Amy Houseman used human gut metagenomes and identified a putative cryptic AMP candidate in multiple metagenomes from an individual. The antimicrobial properties of this candidate, named HG4, were predicted through measurements of its amphiphilic profile and it was found to seemingly originate through proteolysis with intestinal proteases from a protein produced by P. melaninogenica.

In our latest work, we aimed to computationally identify if cryptic AMPs are being produced by prokaryotes within various environments, specifically utilising the proGenomes2 dataset. After attempting to identify potential examples of cryptic AMPs, we then aim to find additional evidence that these are actual occurrences. We assessed the position of each candidate AMP within its precursor protein, its antimicrobial score and the possibility of its release through proteolysis, using known enzymes.

Our data

Our research utilises the proGenomes2 representative genome dataset and Celio Dias Santos Junior's AMPsphere dataset of antimicrobial peptides. The set of representative genomes in proGenomes2 contains 12,221 microbial genomes that have been selected for non-redundancy (Mende et al., 2020). AMPsphere is a dataset of antimicrobial peptides predicted from meta- and microbial genomes by Macrel, a classification pipeline that identifies high-quality AMP candidates (Santos-Júnior et al., 2020).

We aligned AMPsphere against proGenomes2, using MMseqs2 - a highly sensitive, yet fast search tool designed for use on metagenomic data (Steinegger and Söding, 2017). Following alignment, we filtered our data to only include hits with a q-coverage and identity of 100% and an e-value ≤10e-5. Thus, we only consider exact matches between AMPs from AMPsphere and larger proteins from proGenomes2.

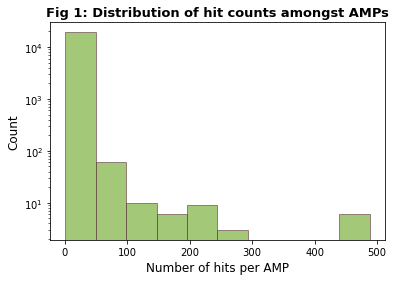

After filtering, we had 54,396 hits and detected a total of 19,399 unique AMPs. The distribution of hits per AMP is seen in Figure 1; while most AMPs had few hits, some outliers had notably more, with 6 having 488 hits each. This is shown more clearly in Figure 2.

What we found out about prokaryotic cryptic AMPs

Cryptic AMPs mainly occur near the end of prokaryotic protein sequences

We aimed to systematically examine where our cryptic AMP candidates occur within our precursor proteins as, while prior research into examples of cryptic AMPs has shown that these cryptides occur at a variety of positions within their precursor proteins, there is no clear understanding of the distribution of AMP positions within precursor proteins. Understanding this distribution is especially relevant as past research into cryptic AMPs has found that certain regions of precursor bacterial proteins have a positive charge; something we know can be linked to antimicrobial properties. Therefore, if cryptic AMPs frequently occur in such regions of their precursor proteins, it suggests that their cationic nature may be associated with their antimicrobial properties.

A protein can be divided into the N-terminal, Internal and C-Terminal regions. The C-Terminal - the end region of a protein - has previously been found to be positively charged in bacterial proteins (Greenward and Perham, 1989). This positive charge is also seen in the C-Terminal of eukaryotic proteins and cryptic peptides have been found to be produced from these regions (Park et al., 2009). Given that the cationic nature of AMPs is central to their antimicrobial ability, it was worth investigating the proportion of cryptic AMPs originating from the C-Terminal of a precursor protein. In addition to this, prior research has also shown some cryptic AMPs originating from the N-Terminal; Pizzo et al. report that cryptic AMP bovine lactoferricin originates from the N-Terminal of bovine lactoferrin, while the additional cryptic AMP lactoferrampin originates from the C-Terminal of bovine lactoferrin (Pizzo et al., 2018).

Our investigation categorised the location of each cryptic AMP within its precursor protein into N-Terminal, Internal or C-Terminal based on its starting position within the precursor protein’s sequence. We set various thresholds of what constituted the N- and C-Termini, ranging from 15% to 45% from the start or end of the precursor protein. The results from this can be seen in Figure 3a-c:

Our results show that the modal location within the precursor protein for the cryptic AMP candidates is the C-Terminal, a statement that is robust to the exact definition of C-terminal used: even when the C-Terminal is defined as only constituting the final 15% of the precursor protein sequence, as in Figure 3a, 40% of all cryptic AMPs are found here. When the C-Terminal is defined as the final 45% of the protein sequence, nearly 65% of cryptic AMPs are found here.

The high proportion of cryptic AMPs in the C-Terminal links to previous research that has highlighted this region's positive charge and the existence of cryptic peptides here, therefore suggesting that these AMP candidates could be utilising this positive charge for antimicrobial purposes. It is also notable that disproportionately few cryptic AMP candidates are located in the internal 40% or 10% of precursor proteins (see Figures 3b and 3c), while small relative increases in the proportion of AMPs located in the N-Terminal despite large threshold increases suggest that the AMPs within the N-Terminal are largely located towards the very start of the precursor protein sequence.

Simple measures emphasise some candidates' antimicrobial potential

In order to better estimate the antimicrobial cryptic AMP candidates we identified, we assessed their absolute relative antimicrobial scores (ARAMS). This measure can assess the potential antimicrobial properties of a cryptic peptide by establishing if it follows structural rules of thumb for peptides whose antimicrobial properties have been validated in a wet-lab environment. While ARAMS is far more simplistic than the machine learning methods used by Macrel for AMP prediction, it nevertheless will provide a selection of cryptic AMP candidates that are highly likely to have straightforward antimicrobial properties in real life.

The ARAMS of a protein attempts to computationally quantify its antimicrobial properties through an analysis of its amino acid composition, taking into account its length, net charge and hydrophobicity among other factors (Kane et al., 2017). We calculated matrices of ARAM scores for all 54,396 precursor proteins in our dataset, varying start position and window length to attempt to quantify the antimicrobial potential for every possible cryptic protein within each precursor protein. An example of one of these matrices is visualised in Figure 4, showing window length on the x axis and start position on the y axis. Lighter colours denote higher ARAMS values, so the cryptide with the highest antimicrobial potential here starts approximately 250 amino acids into the precursor protein’s sequence and is approximately 98 amino acids long.

We thus aimed to compare the relative antimicrobial strength of the cryptic AMP candidates we identified through alignment with the other potential cryptides around them. We identified the 90th and 95th percentile ARAM scores within each protein matrix and recorded if our cryptic AMP candidate met either of these values. Figure 4 also shows how ‘hotspot neighbourhoods’ exist within our matrices; areas with strong antimicrobial potential. We aimed to see if the cryptic AMP candidates were located within or near hotspot neighbourhoods, as this strengthens the case for a cryptic AMP within this precursor protein around this location, even if slight issues had occurred with identifying its exact position. We defined the hotspot level of a neighbourhood as the level of the majority of its constituents.

Our analysis of ARAMS matrices shows that relatively few of our cryptic AMP candidates achieve scores in the ‘hot’ zones of the 90th and 95th percentiles respectively - only just over 10% of candidates have scores equal or above the 90th percentile score of their matrix. This can be seen in Figure 5a. However, this number doubles when looking at the number of candidates within hotspot neighbourhoods, with nearly 20% of AMP candidates existing in hotspot neighbourhoods. The difference can be seen when comparing Figure 5a to Figure 5b, which shows the number of hotspot neighbourhoods near cryptic AMP candidates.

Overall, we found that a minority of our 54,396 cryptic AMP candidates therefore have high ARAM scores (5,563) or occur in high ARAMS neighbourhoods (10,586). This highlights thousands of cryptic AMP candidates from prokaryotic precursor proteins that meet simple in silico measures of antimicrobial potential, suggesting that they would be especially strong candidates for further wet-lab investigation.

Most AMP candidates can be released through proteolysis

Finally, we investigated if known enzymes were capable of freeing our cryptic AMP candidates from their precursor proteins. Even if the sequence of an AMP occurs within a larger protein sequence, this will not become a cryptic AMP unless it can somehow be released from the precursor protein. It was therefore necessary to assess if our cryptic AMP candidates could be released through proteolysis.

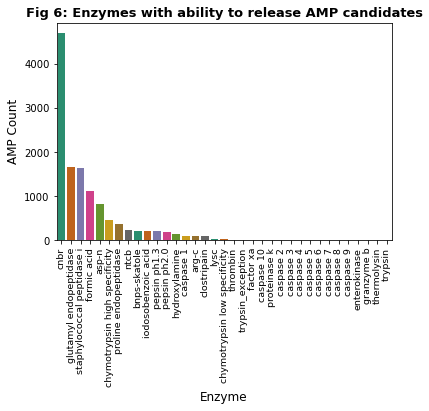

We used Pyteomics to assess if enzymes could cleave our cryptic AMP candidates from their precursor proteins. A total of 33,590 of our cryptic AMP candidates (61.8% of 54,396) could be released in this way. This analysis, showcased in Figure 6, found that 35 different enzymes have the potential to release cryptic AMPs within our dataset, with the 4 most common (CNBr, Glutyl endopeptidase, Staphylococcal peptidase I and Formic acid) each possibly able to release over 1000 different cryptic AMPs. CNBr, or cyanogen bromide, accounts for 35% of the total potential cleavages recorded in our analysis and has previously been found to be produced by microbes (Vanelslander et al., 2012). Interestingly - when denoting the last 40% of a protein sequence as the C-Terminal - approximately 95% of all cryptic AMPs candidates released by CNBr occur in the C-Terminal, compared to only around 60% of all candidates being located here.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have found evidence that cryptic AMPs occur within proteins produced by prokaryotes. These AMPs seem to be predominantly located in the C-Terminal region of proteins, which ties into past research that has shown that this region is positively charged; relevant as this positive charge provides antimicrobial properties. 10-20% of our cryptic AMP candidates additionally either had a high ARAM score or were located in an ARAMS hotspot zone, which further strengthens their viability. Additionally, a majority of our candidates (33,590 out of 54,396) could theoretically be released through proteolysis, again strengthening the viability of these candidates. This makes it very possible that cryptic AMP production by prokaryotes is a real phenomenon, although more research is needed to better understand its scope and intricacies.

Bibliography

Autelitano, D. J., Rajic, A., Smith, A. I., Berndt, M. C., Ilag, L. L. and Vadas, M. (2006) ‘The cryptome: a subset of the proteome, comprising cryptic peptides with distinct bioactivities’, Drug Discovery Today, 11: 306-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2006.02.003

Bradshaw J. (2003). ‘Cationic antimicrobial peptides: issues for potential clinical use’, BioDrugs: clinical immunotherapeutics, biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy, 17(4): 233–240. https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200317040-00002

Greenwood, J., & Perham, R. N. (1989). ‘Dual importance of positive charge in the C-terminal region of filamentous bacteriophage coat protein for membrane insertion and DNA-protein interaction in virus assembly’, Virology, 171(2): 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6822(89)90613-290613-2)

Mende, D. R., Letunic, I., Oleksandr M Maistrenko, O. M., Schmidt, T. S. B., Milanese, A., Paoli, L., Hernández-Plaza, A., Orakov, A. N., Forslund, S. K., Sunagawa, S., Zeller, G., Huerta-Cepas, J., Coelho, L. P. and Bork, P. (2020) ‘proGenomes2: an improved database for accurate and consistent habitat, taxonomic and functional annotations of prokaryotic genomes’, Nucleic Acids Research, 48(1): 621–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz1002

Pane, K., Durante, L., Crescenzi, O., Cafaro, V., Pizzo, E., Varcamonti, M., Zanfardino, A., Izzo, V., Di Donato, A. and Notomista, E. (2017). ‘Antimicrobial potency of cationic antimicrobial peptides can be predicted from their amino acid composition: Application to the detection of “cryptic” antimicrobial peptides’, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 419: 254-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.012

Park, T. J., Kim, J. S., Choi, S. S., & Kim, Y. (2009). Cloning, expression, isotope labeling, purification, and characterization of bovine antimicrobial peptide, lactophoricin in Escherichia coli. Protein expression and purification, 65(1): 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2008.12.009

Pizzo, E., Cafaro, V., Donato, A. D., Notomista, E. (2018) ‘Cryptic Antimicrobial Peptides: Identification Methods and Current Knowledge of their Immunomodulatory Properties’, Current Pharmaceutical Design, 24: 1054-1066. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180327165012

Roscetto, E., Contursi, P., Vollaro, A., Fusco, S., Notomista, E., and Catania, M. R. (2018). Antifungal and anti-biofilm activity of the first cryptic antimicrobial peptide from an archaeal protein against Candida spp. clinical isolates. Scientific reports, 8(1), 17570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35530-0

Santos-Júnior, C. D., Pan, S., Zhao, X-M. and Coelho, L. P. (2020) ‘Macrel: antimicrobial peptide screening in genomes and metagenomes’, PeerJ, 8:e10555. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10555

Steinegger, M. and Söding, J. (2017) ‘MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets’, Nature Biotechnology, 35:1026–1028. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3988

Vanelslander, B., Paul, C., Grueneberg, J.,Prince, E. K., Gillard, J., Sabbe, K., Pohnert, G. and Vyverman, W. (2012). ‘Daily bursts of biogenic cyanogen bromide (BrCN) control biofilm formation around a marine benthic diatom’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(7): 2412-2417. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1108062109

Copyright (c) 2018–2025. Luis Pedro Coelho and other group members. All rights reserved.